Wednesday August 13, 2025

By Mohamed Farah Hussein

In the wake of prolonged conflict and the collapse of the centralized system of governance, Somalia’s externally imposed federalism has proven to be anything but political remedy. More than just a constitutional arrangement, can federalism represents the nation’s quest to reconcile clan allegiances with state-building ambitions? As international actors weigh in and regional models like Ethiopia’s affer cautionary tales, Somalia stands at a crossroads — shaping a governance system that must reflect its own history, identity, and future aspirations.

Regional Perspectives: Is Ethiopia’s Federal model compatible with Somalia’s unique sociopolitical landscape?

In exploring federalism within the Horn of Africa, Ethiopia often comes to the fore as a regional pioneer. It’s ethnic(qowmiyado)-based system has sparked debate across neighbouring states — including Somalia, where federalism has only complicated the political landscape.

A Quick Look at Ethiopia’s Model of Federalism

Ethiopia’s 1995 constitution introduced an innovative system of ethnic federalism, dividing the country into regional states based on ethnolinguistic identity. These states possess:

• Their own constitutions, Presidents as head of state and parliaments

• Authority over language, education, and local governance

• The constitutional right to secede (Article 39)

This arrangement gave Ethiopia’s historically marginalized groups autonomy, but also fuelled political fragmentation and interregional conflicts.

Challenges in Applying The Ethiopian Model to Somalia

Somalia’s societal divisions are not ethnic but clan-based, making Ethiopia’s rigid ethnicity-based boundaries impractical. Key concerns include:

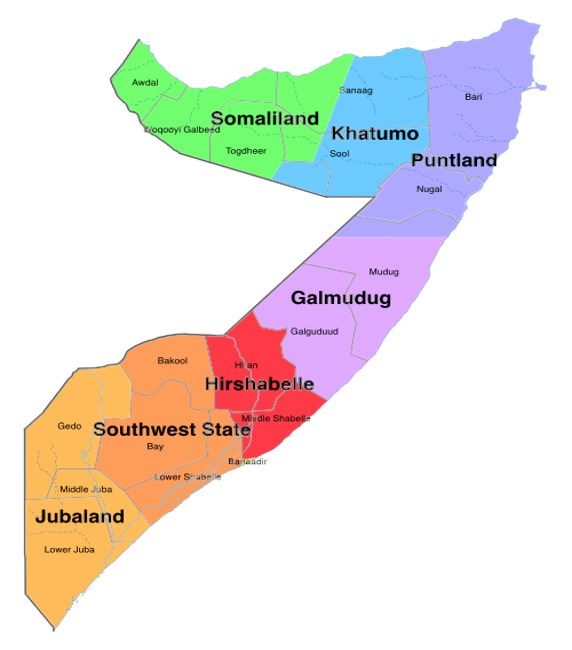

• Clan mobility: Somali clans often span multiple regions, complicating territorial claims – Clear examples include; the divided city of Galkayo and the current conflict surrounding SSC Khatumo, Somaliland and Puntland.

• Fragmentation risk: Ethiopia’s model has emboldened secessionist movements — a dangerous precedent for Somalia, still healing from decades of disunity

• Central weakness: Excessive autonomy to federal member states (FMSs) has paralyzed national cohesion and decision making – amplifying rivalries such as the one ongoing between the Federal government, Jubaland and Puntland.

Main Criticisms of Foreign Involvement in Somalia

Foreign actors have long played a central role in Somalia’s political and security landscape — but their involvement has not always been welcomed. Geopolitics, history, and strategic interests in the Horn of Africa make regional states feel uneasy about a strong, unified Somalia. In this regard, Somalis have long realized that the intentions of foreign involvement in Somalia has never been to help Somalia reemerge from chaos but rather a policy of containment and to maintain status-quo.

Some highlights of these criticisms;

Federalism as a Foreign Blueprint: Somali intellectuals believe that federalism was externally imposed rather than organically developed, leading to confusion and resistance in some regions.

Maritime Power: Somalia’s vast coastline and Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) offer immense potential in fisheries, oil, and shipping. Regional powers may worry leverage from these resources may lead to Somali dominance in the region.

Counterterrorism Rivalries: Countries like Ethiopia and Kenya have used security risks posed by Al-Shabab to their countries to justify their interference in Somalia affairs. If Somalia takes full control over its security apparatus, it could reduce their influence or expose past interventions to scrutiny.

Proxy Influence: Somalia’s internal divisions have allowed neighbouring states to back factions or leaders aligned with their interests. A unified Somalia could disrupt these proxy arrangements.

Port Competition: Somalia’s ports (e.g. Berbera, Bossaso, Kismayo, Mogadishu) could rival regional hubs like Dubai, Mombasa or Djibouti. These countries fear losing trade dominance if Somalia modernizes its infrastructure.

Aid and Investment Realignment: A stable Somalia could attract direct foreign investment, shifting donor priorities away from neighbouring states that currently benefit from Somalia’s instability. Almost, all foreign aid to Somalia goes via Kenya which contributes substantially to Kenya’s economy.

Top-Down Peacebuilding: International efforts often prioritize institutional frameworks over grassroots reconciliation, sidelining traditional Somali conflict resolution mechanisms.

Selective Engagement: Foreign powers have backed rival factions, fuelling internal divisions. For example, Ethiopia and Kenya have supported different regional actors within Somalia, usually undermining the authority of the federal government.

Drone Strikes and Collateral Damage: Military interventions, particularly by Ethiopia and the U.S have attracted international terrorist groups to Somalia and have drawn criticism for civilian casualties and lack of transparency.

Short-Term Fixes: Critics argue that aid often focuses on immediate relief rather than long-term development, creating cycles of dependency. Phrases such as “millions of Somalis are on the brink of starvation unless the world …” is frequently used by NGOs.

Corruption and Waste: UN missions like UNOSOM II were plagued by logistical failures, financial mismanagement, and poor coordination with local actors.

Donor Fatigue: Inconsistent funding and shifting priorities have left Somali institutions vulnerable and under-resourced.

Foreign Troop Presence: The presence of AU and foreign troops is seen by some as compromising Somalia’s autonomy, especially when troop-contributing neighbouring countries pursue their own agendas. Terrorist groups also use the presence of foreign troops to justify their struggle.

Geopolitical Rivalries: The involvement of Middle Eastern powers (e.g. UAE, Qatar, Turkey) has introduced regional rivalries into Somali politics by sponsoring rival political actors, complicating peace and stability efforts.

Why Decentralisation Became Fragmentation in Somalia

1.Constitutional ambiguity on the division of powers

The 2012 Provisional Constitution leaves many core issues — especially allocation of powers and resources between the Federal Government and Federal Member States (FMSs) — undefined or to be negotiated, producing endless disputes and ad-hoc bargaining instead of clear rules.

2. A federal model built around clans and ad-hoc territories rather than firm administrative boundaries

Instead of territorially coherent, institutionally-strong regions, Somalia’s “federal” units have in practice often been created around clan power-bases and local elites who act like “mini-presidents,” which fragments authority and weakens national cohesion. This turns federalism into a legitimization of clan patronage rather than a vehicle for stable decentralised governance.

3. Competing security providers and lack of monopoly on force

Federal member states, regional militias and non-state actors (most importantly Al-Shabab) control large swathes of land; meanwhile, regional forces act independently of Mogadishu. The result is a patchwork of authority, limited mobility for officials, and uneven service provision. That undermines both the federal centre’s credibility and the capacity of FMSs to govern.

4.Chronic fiscal disputes and weak fiscal federalism

Revenue collection, natural resource contracts and spending powers are highly contested. There’s weak, inconsistent revenue-sharing and heavy donor dependence, which produces competition over scarce money and fuels political friction between Mogadishu and member states.

5.Political fragmentation, contested statehood and ongoing inter-state disputes

The creation of new member states (and competing claims over regions such as Sool, Sanaag and parts of Jubaland) keeps reigniting tensions between Mogadishu and regional capitals (e.g., Puntland, Jubaland), which often escalates into political standoffs or brinkmanship instead of institutional compromise.

6. External actors and uneven international engagement

Different foreign partners sometimes bypass Mogadishu or work directly with regional authorities; shifts in external military and aid policies (and the ebbing of AMISOM-type support) create openings for rivals (state and non-state) and make coordination harder. Changes in donor engagement have affected the balance of power and security capacity.

7. Weak institutions and lack of genuine local democracy

Most local administrations are built around a strongman; governance is often top-down or elite-driven. Without accountable institutions at both federal and regional levels, federalism becomes a vehicle for elite bargaining rather than delivering services or legitimacy to citizens.

Somalia’s Federal Experiment has failed and begs for change of course – A Path Built from Within

Rather than replicate Ethiopia’s blueprint of federalism, Somalia is better served by a context-sensitive system — one that acknowledges clan dynamics, promotes inclusivity, and builds resilience against external manipulation. The country needs a political reset that reflects its unique social fabric and supports nation building.

These include:

• Strengthening regional governance without undermining central authority

• Building institutions that serve all citizens without institutionalizing division

• Promoting shared national identity while respecting local identity

Somalia’s journey towards a cohesive political system remains a work in progress. While external models and international actors have influenced its course, the country’s future hinges on developing a homegrown framework — one that transcends clan divisions, reinforces nation state, and reflects on Somali values.

Very few self-centred Somali politicians still cling on the Ethiopian Federal Model but the evidence is clear, Somalia needs to abandon a political course that is not working for it and come up with a new political approach that serves its national interest. A political system is not simply a structure but a mirror of the national identity, resilience, and inclusivity. In this regard, Somalia has to choose between the following 2 options;

1. The United States of America model of federalism where regional states are granted full autonomy to deliver all essential services to their citizens. The head of the regional state is the locally elected governor. All key positions are locally elected and are accountable to the locals. The powers and the responsibilities of the member states and the federal government are clearly defined in the constitution without overlapping each other.

2. Go back to the old system of 18 regions but with full decentralisation this time around. The local people must be allowed to self-determine their future without interference from the central government. This model is similar to option 1 above (the American Federalism) but with autonomous regions within one nation state. Option 2 is more suitable for Somalia, taking into account its political and economic situation.

In conclusion, Allah (SWT) has blessed Somalia with Islam and one of the world’s richest land and sea. But Allah (SWT) also told us that, “He does not change a nation (for the better or worse) unless the nation changes itself from within”. To harness Somali heritage, resilience, and creativity to shape all-inclusive, peaceful, and prosperous Somalia, it is my humble opinion that Somalia has no choice but to choose between the above 2 viable political options to elevate itself from clan division and build an all-inclusive nation state.

References (APA Format)

1. Coe, B., & Nash, K. (2022). Security governance and UN-AU partnership in Somalia. PeaceRep. https://peacerep.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Somalia-Report-Digital.pdf

2. Dahir, A., & Sheikh Ali, A. Y. (2024). Federalism in post-conflict Somalia: A critical review. Regional and Federal Studies. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/13597566.2021.1998005

3.Elmi, A. (2021). Federalism and clan rivalries in Somalia. HORN Institute Bulletin. https://horninstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/HORN-Bulletin-Vol-VIII-%E2%80%A2-Iss-III-%E2%80%A2-May-June-2025.pdf

4. Lewis, I. M. (2002). A modern history of the Somali. Oxford University Press.

5. Mahmoud, S. (2025). How foreign intervention destabilised Somalia. Geeska. https://www.geeska.com/en/how-foreign-intervention-destabilised-somalia

6. Mumbere, M.J. (2023). Federalism and Political Stability in Somalia. Nile University of Science and Technology. Download the study

7. Mubarak, M., & Mosley, J. (2014). On Federalism and Constitutionality in Somalia: Difficulties of Post-Transitional Institution-Building Remain. African Arguments. https://africanarguments.org/2014/02/on-federalism-and-constitutionality-in-somalia-difficulties-of-post-transitional-institution-building-remain-by-mohamed-mubarak-and-jason-mosley/

8. Warsame, A. (2021). Can Somalia Restore Faith in Its Federal Agenda? LSE Africa at LSE. https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/africaatlse/2021/11/29/can-somalia-restore-faith-in-its-federal-agenda-federalism-governance-decentralisation/

9. Noor, A. (2014). Clan Federalism: The Worst Option for State-Building in Somalia. Modern Ghana. https://www.modernghana.com/news/573138/clan-federalism-the-worst-option-for-statebuilding-in-somal.html

10. Global Governance Africa. (2021). Federal Feud: Escalating Tensions Between Somalia’s Federal Government and Jubaland. https://gga.org/federal-feud-escalating-tensions-between-somalias-federal-government-and-jubaland/

11. Parker, C. (2025, May 27). As U.S. Draws Down in Somalia, Turkey Expands Role. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2025/05/27/somalia-al-shabab-american-troops-trump/

12. Oloo, F. (2022). Peacebuilding in Somalia: Local Realities, Federal Aspirations and the Shifting Role of External Support. RSIS International. https://rsisinternational.org/journals/ijriss/articles/peacebuilding-in-somalia-local-realities-federal-aspirations-and-the-shifting-role-of-external-support/

This piece was written by Mohamed Farah Hussein, who is a lecturer in Business at Newham College London, UK, he can be reached via email: mrashid114@yahoo.com