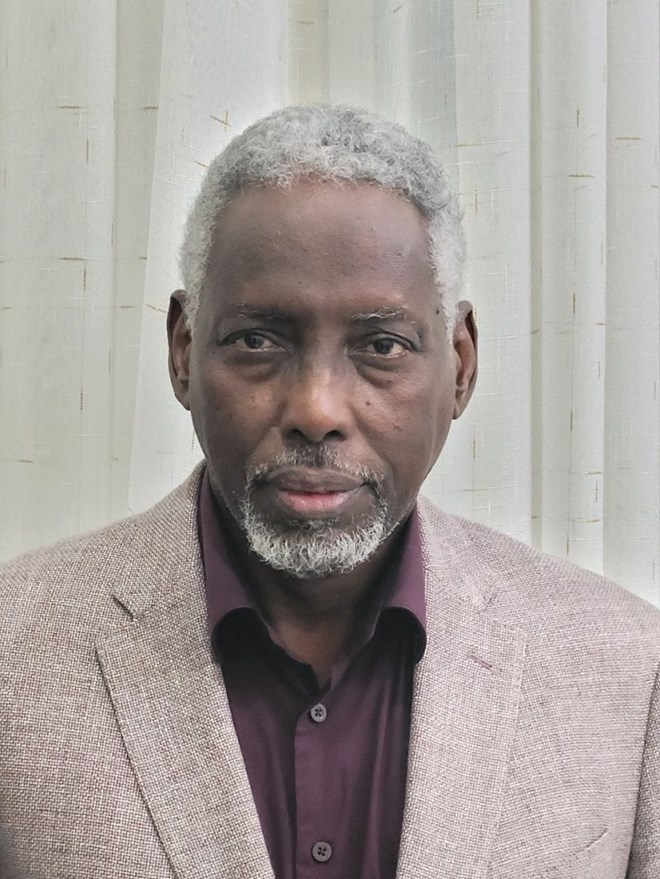

By Dr. Abdurahman Baadiyow

Saturday August 23, 2025

The story of Somalia does not open like a dusty record book—it bursts forth like a storm on the horizon, alive with cries of resistance and the heartbeat of a people who would not be broken. Between 1948 and 1950, in distant capitals under the dim glow of chandeliers, foreign powers weighed Somalia’s fate like traders over spoils, debating whether to return it to Italy’s grasp, their whispers dripping with betrayal as though the nation were nothing more than a discarded piece of empire. Yet beyond those velvet halls, Mogadishu’s streets trembled beneath the footsteps of thousands, banners rose, and voices thundered like crashing waves, while at the United Nations a lone, defiant vote cut through the silence and shattered the schemes of the powerful. In that collision of whispered plots and roaring crowds, history revealed its deepest truth: Somalia’s freedom was not a gift bestowed, but a legacy carved in defiance, forged in sacrifice, and seized by a people who refused to surrender their destiny.

On 10 February 1947, beneath the glittering chandeliers of Paris, Italy laid down the last remnants of its empire, relinquishing claims over Libya, Eritrea, and Somalia, and bowing to Ethiopia’s independence. For Somalia, however, the silence was deafening—its fate suspended, a nation left hanging between hope and betrayal. By 1948, the Four Powers—Britain, France, the United States, and the Soviet Union—sent a fact-finding commission to Mogadishu, where delegations of political parties, clan elders, and civic leaders debated the nation’s future. Somali political parties disagreed the way forward to Somalia. But beyond the polished hearing rooms, tension thickened like storm clouds. The SYL, uncompromising in its opposition to any return of Italian rule, fanned the embers of anger into flame. On 11 January, the city erupted. What began as chants and banners twisted into a torrent of stone and blood; streets became battlefields, and in a day of fury, 52 Italians and 14 Somalis fell, hundreds more wounded. Mogadishu convulsed—not just in violence, but in a raw, unshakable declaration: Somalia’s destiny would not be dictated by outsiders.

On 24 September 1948, after months of bitter wrangling and endless debate, the Four Powers gathered once more in Paris to confront the thorny question of Italy’s collapsed empire. The report of the commission lay before them, heavy with conflicting views, and the atmosphere was thick with fatigue, rivalry, and the unspoken weight of responsibility. Each delegation clung to its own vision of Africa, knowing that the destinies of Libya, Eritrea, and Somalia hung in the balance. Through the night the negotiations dragged on, voices rising, tempers fraying, until exhaustion and the sheer complexity of the problem forced a reluctant compromise. In a joint communiqué, the Powers pushed the burden upward, passing it to the Secretary-General of the United Nations. That very day, at the 142nd ordinary meeting of the Assembly, the matter was referred to the First Committee—the Political and Security Committee—where the fate of millions would be contested not by swords or barricades, but by speeches and votes. For Somalia, whose people already stirred with both hope and unease, it was a turning point: the struggle for their future had shifted from the restless streets of Mogadishu to the echoing halls of international diplomacy, where strangers far from their homeland would now attempt to shape a nation’s tomorrow.

On 4 May 1949, in the smoke-filled, shadowed chambers of London diplomacy, Ernest Bevin and Carlo Sforza sealed a bargain that would shape the fate of Italy’s former colonies. The Bevin–Sforza Agreement, crafted behind closed doors, was swiftly dispatched to the UN’s First Committee, and by 11 May the path was cleared for its arrival at the General Assembly. Its terms were stark: Somalia, torn from Italy in the chaos of World War II, was to be handed back under Italian administration, cloaked in the language of a UN trusteeship of indefinite duration—a quiet hope in Rome that decades of control still lay ahead. For Italy, it promised redemption and the restoration of wounded colonial pride; for Bevin, it marked the burial of Britain’s vision of a Somali union, repackaged as diplomatic success. But as the two ministers clasped hands in satisfaction, their agreement reverberated far beyond London’s polished halls, sending shockwaves through Mogadishu, where the people—scarred by the memory of conquest—recognized in it not triumph, but betrayal.

In the days after the Bevin–Sforza Agreement sought to return Somalia to unrestricted Italian administration—a scheme wrapped in diplomacy but felt by Somalis as betrayal—the United Nations chamber at Lake Success became the stage for a defiance that would echo across Africa. Abdullahi Isse, secretary general of the Somali Youth League, fought fiercely against the plan, even as its supporters were confident it would sail through. Yet on 17 May 1949, the tide of history shifted: Haiti’s Ambassador Émile Saint-Lot, a close ally of Abdullahi Isse, cast a lone and decisive “Against,” defying his government, the great powers and grounding his vote in principle and solidarity. The next day, he told the General Assembly that Haiti, bound by its kinship with African peoples, could not endorse a resolution that risked bringing ruin upon them. His stand reverberated across the Atlantic; Mogadishu erupted in jubilation as crowds filled the streets, and the SYL hailed him as “the man who defended Somali honor.” In those charged years of riots, treaties, and decisive votes, one truth blazed through: Somalia’s destiny would not be written by distant powers but seized through the defiance, determination, and unyielding will of its own people.

Subsequently, by September 1949, as the Fourth Session of the UN General Assembly opened in New York, Somalia’s fate had shifted from whispered deals in distant capitals to the voices of its own people standing on the global stage. Delegates from the SYL and the Conferenza, a pro-Italian parties, took their place before the world, the SYL denouncing any return of Italian rule while the Conferenza backed it, each word carrying the restless heartbeat of a nation. Yet in the hushed halls of the Political Committee on 4 October, the final decision was nearly sealed: Somalia would again fall under Italian administration. The next day, 5 October, that verdict struck Mogadishu like a thunderclap. Women pounded pots and pans in defiance, men hoisted placards screaming, “We will not go back in chains!”—and the city erupted. Stones clashed against rifles, blood stained the dust, and by nightfall 7 Somalis lay dead, 13 wounded, and 300 dragged away in chains. SYL leaders were imprisoned or exiled, but their courage could not be extinguished; it throbbed in every heart that longed for freedom. That day was immortalized as Dhagaxtuur— “the Stone Throwing”—and a monument later rose at the site, a lasting testament not only to loss, but to a people who refused once more to bow to their former masters.

Even though the monument stands tall to commemorate the event and honor the sacrifice made, it remains a silent reminder of what history has forgotten. We do not know the names of those who gave their lives—their identities lost in the passing of time, their faces absent from the record. They are remembered not as individuals, but as a collective spirit of defiance, anonymous martyrs whose courage shaped the course of their nation. The absence of their names deepens the tragedy, for behind every unknown figure was a son or daughter, a father or mother, whose story deserved to be told. Yet, even unnamed, their sacrifice endures, etched not in stone but in the living memory of a people who continue to walk in the freedom that those forgotten heroes helped secure.

On 21 November 1949, the United Nations unveiled its uneasy compromise: Resolution 289. Somalia would be placed under Italian administration once more, but this time clothed in the legitimacy of a UN trusteeship—a decade of oversight supervised by a committee of Egypt, Colombia, and the Philippines, with the stated purpose of preparing the nation for independence. In New York, the resolution passed amid polite applause, celebrated as a cautious diplomatic victory. But in Mogadishu, the verdict struck like a spark on dry tinder. The streets erupted with cries of anger and defiance: “We asked for freedom today, not tomorrow!” While pro-Italian factions celebrated what they saw as their triumph, the Somali Youth League rose to meet the fury with clarity and resolve, rallying the crowds with words that would echo for generations: “If trusteeship is forced upon us, we will turn it into a school for independence. Ten years will not break us—ten years will make us.” Somali newspapers captured the defiant mood in stark, unforgettable lines: “Our demand was freedom today. The world gave us freedom tomorrow. We will make tomorrow arrive.” In that fraught balance between imposed compromise and unyielding aspiration, the spirit of a nation did not waver—it burned fiercer, forging its determination into a force no foreign mandate could extinguish.

On 1 April 1950, the Italian tricolor once again fluttered above Mogadishu. Though the calendar marked April Fools’ Day, there was nothing funny for Somalis as Italian administrators marched back into offices months before the official signing of the trusteeship. Anger rippled through the streets, and in the bustling marketplace, a banner mocked the day: “April Fools: Somalia Handed to Italy.” Yet beneath the fury, a quiet, resolute determination was taking root. The SYL declared, “This is not the end. These ten years will be our proving ground.” Elders leaned close to the youth, urging, “Do not waste this decade. Let it be our training for independence.” Across towns and villages, Somalis resolved to transform every Italian policy, every school, every council into a stepping stone toward sovereignty. What was meant to revive colonial authority instead became, in Somali hands, a crucible of nation-building, a nursery where the leaders and vision of an independent Somalia were forged.

From the smoke-filled chambers of the Four Powers in 1948, where distant diplomats treated Somalia’s fate like a pawn on a chessboard, to the fiery streets of Mogadishu convulsing against the Bevin–Sforza betrayal, from the strong advocacy and lobby of the Abdullahi Isse and solitary, defiant vote of Émile Saint-Lot in New York to the bitter compromise of trusteeship in 1950, Somalia’s march toward independence was a saga of betrayal and defiance, despair and hope. The world offered only a timeline, a decade under foreign supervision, yet the Somali people filled those years with purpose and resolve. They surged through streets, held clandestine councils, and raised their voices in unison, chanting “Gobonimo ama Geeri!”—Freedom or Death—until the walls of colonial authority began to crack. Ten years later, in 1960, Somalia rose—not because independence was granted from above, but because it was seized, demanded, and forged by the unwavering courage of every citizen, every petition, every heartbeat of a nation refusing to be silenced.

In the midst of today’s political storms—where elites quarrel over power and the nation bleeds for their ambition—Somalis must let the past cast its light upon the present, for their forefathers once stood in a darker storm and carved a path forward. In those years, when the fate of Somalia was bartered in foreign halls, it was not the signatures of diplomats that kept hope alive, but the defiance of a people who filled the streets of Mogadishu, the courage of the SYL, and the sacrifice of ordinary men and women who demanded independence not tomorrow but today. They transformed betrayal into resolve, delay into determination, and trusteeship into a stepping stone toward independence. Their struggle tells us one truth that must not be forgotten: nations are not built on the quarrels of elites but on unity of purpose and the willingness to sacrifice for something greater than oneself. And so, as the curtain of history draws from past to present, Somalia’s survival and future will once again depend on whether its people—and its leaders—can rise above division and claim, as their forefathers did, a tomorrow worthy of their courage.

Dr. Abdurahman Baadiyow

abdurahmanba@yahoo.com