Wednesday August 27, 2025

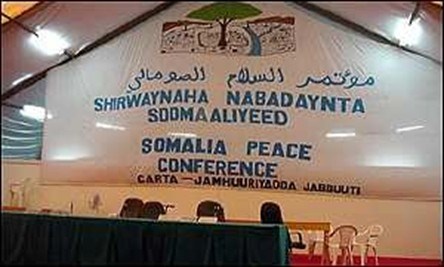

The Arta Peace Conference, held in

Djibouti in 2000, concluded 25 years ago today. After a series of failed

attempts, the Arta peace conference stood out as the first Somali-led peace initiative,

bringing together a broad range of participants, including clan

representatives, civil society actors, and religious leaders. The conference

aimed to restore the central government by creating a transitional constitution

and parliament, pursuing a dual agenda of reconciling warring factions and

addressing political divides. This culminated in the election of Abdiqasim

Salad Hassan as president of the new Transitional National Government (TNG).

Two and a half decades later, we

have to ask: What did Arta actually achieve? Is Somalia any closer to becoming

a stable, self-sustaining state? And most importantly, how long can the current

political deadlock last?

A major flaw of the Arta process was

the assumption that a functioning state could emerge simply by first creating

an administration; the top-down approach. The problem with this approach,

whether overlooked or ignored, is that the cyclical nature of administration

leaves little room for genuine state-building. Politicians are consumed by

day-to-day governance, and the time, effort, and political cost required for

deep structural reform are simply too high. A president on a four-year term

with re-election ambitions lacks the time and political will to initiate such a

risky agenda.

As a result, the constitution

remains unfinished, and the process to finalize it is deeply flawed. The

federal system is ill-defined, and political divisions are entrenched. And

despite repeated promises by presidential contenders to complete the constitution

and hold a one-person, one-vote election, they have consistently failed even to

establish the constitutional court needed to resolve legal and constitutional

disputes. This has created a recurring cycle of political crises.

Adding to the crisis are the

relentless security threats from Al-Shabaab. The Federal Government, propped up

by 20,000 foreign troops and shrinking international support, is led by an

incumbent determined to cling to power at any cost, regardless of the damage to

the country. Within a year, this cycle of political crises will inevitably

repeat, bringing with it the same promises and backroom deals and increasing

public cynicism. Furthermore, the persistent allegations of corruption, from

misusing public funds to engaging in land grabs, have eroded the public and

international community's trust in the integrity of Somalia's political

institutions.

Somalia's current path of

elite-driven bargains, persistent security threats, and dependence on foreign

aid is unsustainable. The first step to break this vicious cycle is a radical

change in direction. The way forward begins with initiation of a genuine

grassroots-level reconciliation process and electing a courageous leadership

committed to fight the rampant corruption, investing time and energy in

building durable institutions, confronting security threats, advancing national

interests, and bridging deep political divides. Without genuine transparency

and reasonable level of public trust, any electoral process (most likely

indirect) risks being perceived as predetermined with little or no public

legitimacy, thereby undermining the very foundation of the nation's fragile

democratic transition.

Abdirashid Elmi, PhD, Professor at Kuwait University,

Kuwait, E-mail: ainanh63@yahoo.com

Mohamed Musa, PhD, Professor at Gulf University of

Science and Technology, Kuwait, E-mail: beddel06@gmail.com