Tuesday July 22, 2025

By Bashir M. Sheikh-Ali

A free and responsible media is central to any democracy and vital to nation-building. In democratic societies, the media does more than disseminate information. It fosters transparency, encourages civic participation, and holds leaders accountable. Through the way stories are framed, media narratives help societies define common problems, shared goals, and a collective sense of identity. In a context like Somalia, where the task of rebuilding national cohesion is urgent, media plays a critical role in shaping whether citizens see themselves as part of a shared national project. How stories are told can either bind citizens together, reinforcing the legitimacy of democratic governance, or deepen divisions and alienation.

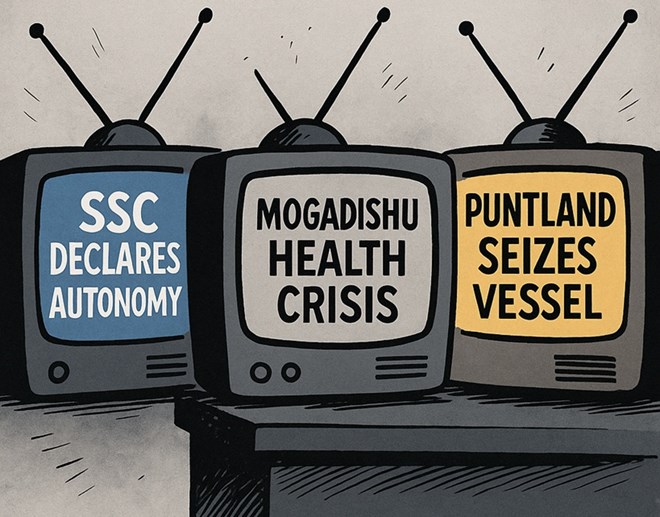

In light of the media’s critical role, Somalia’s current discourse stands out as deeply fractured—reflecting not only political conflict or regional rivalries but also a fragmented way in which stories are told and framed. Rather than constructing a shared national story, much of the reporting observed in outlets such as HiiraanOnline and WardheerNews reinforces division. These vibrant and essential platforms, through their recent coverage from July 1 to July 20, 2025, reveal that Somalis increasingly consume a narrative shaped by competing regions, disconnected elites, divided security forces, isolated humanitarian crises, and episodic diplomatic engagements. This reporting lacks a cohesive thread that connects these developments as part of a single national journey.

Media coverage of state-building vividly illustrates this fragmented narration. Recent reporting on the SSC Khaatumo statehood conference in Las Anod centered almost exclusively on local elders and political figures negotiating among themselves, with little effort to situate the event within the broader context of Somalia’s federalization process or constitutional framework. When elders from Sanaag and Haylaan expressed dissent, their disagreement was framed narrowly as a local dispute, rather than as evidence of a broader incoherence in Somalia’s constitutional process—a process that has allowed regional political projects to advance without reference to national unity or shared governance principles. This style of reporting contributes to the perception that state-building is a purely regional undertaking, shaped by localized actors and interests, disconnected from national institutions or goals. By failing to present these developments as part of a wider national project, media narratives reinforce the sense that Somalia’s state-building efforts proceed in fragmented silos, devoid of coordination or constitutional coherence.

Security reporting reflected this fragmented narration clearly. Recent clashes between Puntland forces and clan militias in Dhahar were reported alongside the federal government’s call for withdrawal, with no mention of a national security strategy. Similarly, the federal forces’ airstrike in Hiiraan and Puntland’s separate announcement of arrests of suspected ISIS operatives were treated as isolated incidents, with no discussion of how they fit into Somalia’s broader security architecture. Puntland’s interception of a vessel near Bareeda’s coast on July 19 was likewise reported as a unilateral Puntland action, with no analysis of federal maritime authority or coordination. Each of these developments was covered as a discrete event, without conveying the absence of a unified security framework or the constitutional questions they raise. This media treatment reinforces the perception that security has become a matter of regional responsibility, managed independently and without national coherence.

Humanitarian reporting during this period reflected the same fragmentation. Articles about housing of displaced families in Mogadishu appeared alongside reports on flooding and displacement in Garowe, yet there was no effort to link them as symptoms of shared national vulnerability or governance challenges. This disconnection leaves readers with the impression that these crises are separate, when in fact they could evidence of the absence of a national disaster preparedness strategy and shared resilience framework. The fractured portrayal contributes to normalizing humanitarian disunity, where national solidarity is neither expected nor demanded.

Public health reporting followed the same pattern of fragmentation. On July 15, HiiraanOnline published that Minister of Health had “issued a nationwide alert over the rapid spread of hepatitis,” warning that the virus could soon overwhelm Somalia’s health system. The article emphasized risky urban and rural areas and the urgent need to expand “testing, vaccination, and public awareness.” Despite using the term “nationwide,” the coverage focused chiefly on the situation in Mogadishu, offering no details on regional outbreaks, prevention efforts, or coordination with member states. By centering the narrative on Mogadishu alone, the reporting subtly implied that the threat was confined to the capital, distancing readers in other regions from its urgency. This framing strengthened the notion that public health is a local issue rather than a shared national concern, masking systemic weaknesses in Somalia’s health infrastructure and normalizing governance that lacks coordination and collective responsibility in dealing with health crises.

Foreign policy reporting during this period further illustrates fragmented narration. Coverage of Somalia’s security pact with the United Kingdom appeared as an isolated development, with no attempt to situate it within a broader discussion of Somalia’s diplomatic strategy or national security objectives. Separately, commentary on Somalia’s potential involvement in Nile Basin politics was presented without linking it to any coherent foreign policy framework. In both cases, there was no evaluation of how these engagements align with Somalia’s national interest or constitutional obligations. The reporting treated these external affairs as unrelated episodes, reflecting and reinforcing the disconnection that also characterizes Somalia’s domestic political discourse. This fragmented portrayal of foreign policy obscures the need for an integrated diplomatic vision and leaves the public with little sense that Somalia speaks with one voice on the world stage.

Opinion columns published during this period reinforce the fragmented narrative environment. Some commentators called for the re-centralization of power in Mogadishu, framing stronger central authority as the answer to Somalia’s governance crisis. Others argued for expanding the autonomy of regional states, presenting decentralization (in the form of confederation) as the path to greater stability. These opposing viewpoints were presented in isolation, with little or no discussion of their implications for Somalia’s already fragile constitutional balance. Instead of encouraging thoughtful debate about how federalism might be repaired or strengthened to function as intended, these opinion pieces advance competing visions that both contribute to fragmentation. In this narrative environment, governance is increasingly portrayed as a binary choice between unilateral centralization or regional disengagement, normalizing the idea that political life must proceed along fractured, disconnected paths.

Political elites play an active role in shaping and amplifying this fragmented discourse, while media reporting has reflected and reinforced this dynamic, often failing to situate the opposition’s views within a broader national context. Coverage of opposition leaders and regional governments regularly portray unilateral actions and rhetoric as ordinary political developments rather than breaches of constitutional norms. For example, when Somaliland’s leadership accused Mogadishu of undermining dialogue in Sool and Sanaag, or when opposition voices criticize federal overreach, reporting often frames these developments as regional grievances without interrogating their constitutional implications. Similarly, when the federal government acts unilaterally without consultation with federal member states (such as when it recognized SSC-Khaatumo or authorizes deployments of security forces in contested areas), media narratives presented these moves as routine exercises of federal authority, neglecting to situate them within a national constitutional framework. By treating these actions and statements as disconnected and unremarkable, the media has contributed to normalizing fragmentation, reinforcing the perception that disunity is an accepted feature of Somali political life, and deepening the public’s sense that governance is a fractured, regionally driven enterprise.

This lack of contextualization extends beyond opposition leaders’ statements to include reporting on the actions of federal member states. There have been frequent reports of states declaring their withdrawal from engagement with the federal government, yet such announcements rarely provoke from the media discussion of their constitutional significance. When these states take unilateral action, media coverage tends to portray them as routine political maneuvers rather than fundamental challenges to the integrity of Somalia’s constitutional framework. Likewise, when federal member states refuse to participate in federal plans, such as election processes, the media often frames these situations as ordinary disputes between regional and federal authorities rather than as signs of a deeper governance crisis. This framing reduces what are, in essence, constitutional confrontations into everyday disagreements, stripping them of their deeper national implications. By consistently failing to situate these developments within the broader constitutional context, reporting allows them to appear as expected features of Somali political life rather than as signs of systemic dysfunction that threatens the foundations of federal governance.

This narrative gap is further compounded by the behavior of the member states themselves, which often articulate their grievances in political or clan terms rather than framing them explicitly as constitutional disputes. This lack of constitutional framing by the state actors involved both shapes and reinforces the way these developments are reported, further normalizing fragmentation.

The cumulative effect of these patterns is a feedback loop where fragmentation in governance is mirrored and amplified by fragmented narration. Media outlets, political leaders, and commentators all participate in sustaining this cycle by portraying events as disconnected episodes, failing to contextualize them within a national framework. The public, shaped by this pattern of reporting, increasingly accepts fragmentation as the inevitable condition of Somali political life.

Yet narration itself could serve as a tool for national repair. Somali media discourse could begin to stitch these disconnected stories into a single national conversation. Reports on SSC-Khaatumo could examine its constitutional implications for federalism. Security coverage could highlight the absence of a unified national command structure and connect regional violence to national policy challenges. Humanitarian reporting could question why Somalia lacks a national disaster preparedness strategy, illustrating how floods and displacement expose shared vulnerabilities. Health reporting could remind readers that disease respects neither clan nor regional boundaries. Foreign policy coverage could evaluate every diplomatic engagement in terms of whether it advances a Somali national interest.

Political elites and commentators could adopt language that emphasizes national cohesion. Civic leaders could convene forums that transcend regional and clan loyalties, focusing on collective challenges. Educational institutions could teach history and civics in ways that cultivate a sense of belonging to a shared Somali story. Religious leaders could use their moral authority to promote collective responsibility and solidarity. Artists, poets, musicians, filmmakers, and writers could tell stories that reflect shared struggles and aspirations.

This transformation alone will not alone resolve Somalia’s deep political and security challenges. Structural problems will persist, and solutions will require negotiation and reform. But without a shared national narrative, no constitutional settlement, security strategy, humanitarian initiative, or diplomatic effort can endure. The crisis of narrative is as urgent as any other crisis Somalia faces. It must be confronted deliberately and consistently if Somalia is to rebuild a future where its people see themselves as citizens of one nation, capable of belonging together in a shared political and moral community. Only by the media insisting that every story contributes to a national story can Somalia begin to reverse the patterns that have normalized division. If the country is ever to achieve unity, its media, political discourse, and public conversation must begin to reflect that aspiration.

The author is a Somali-American lawyer based in Nairobi. The views expressed in this op-ed are his own and do not reflect those of any organization with which he may be affiliated. He can be reached at bsali@yahoo.com.