By Dr. Abdurahman Baadiyow

Saturday September 6, 2025

In the corridors of time, history is never silent—it whispers, it screams, and it is contested in both shadow and light. Writing the past is not merely the recording of events; it is a battle for identity, a struggle over memory, and a fight for the soul of a nation. Some stories shine like torches, celebrated and immortalized, while others are buried in silence by hands that fear the truths they carry. To hold the pen of history is, at its core, to wield a sword: determining who is remembered as a hero and who is condemned as a traitor, which struggles will echo through generations and which will vanish like smoke. Yet this is more than political conflict or a contest for power—it is a moral struggle, where justice, dignity, and recognition matter more than any crown. Every reclaimed story and every truth given voice becomes a beacon against erasure, lighting the way forward and revealing future possibilities. Shaping the past is not just about preserving memory; it is about defining identity, confronting uncomfortable truths, and mapping the legacy that future generations will inherit. Ultimately, the battle over history is a struggle to see ourselves clearly, to honor resilience and courage, and to build a future grounded in the full weight of remembered struggle.

For generations, outsiders have woven distorted narratives of Somali history, portraying Somalis as latecomers to the Horn of Africa—migrants arriving in waves or invaders seizing land that was never theirs, as if their presence were a historical accident without roots. Yet the winds sweeping across Somalia’s ancient plains, the whispered oral poetry passed from elders to youth, and the ruins of forgotten trading ports along the Indian Ocean coast tell a different story: one of a people deeply rooted in this land since time immemorial. Archaeological discoveries such as the Laas Geel cave near Hargeisa, with rock art dating back over 6000 years, testify to early Somalis’ deep connection to land, livestock, and symbolic religion, while the Dhambalin engravings in the northeast depict hunting scenes and pastoral life, revealing the early spread of Cushitic civilization in the region. Excavations at Buur Heybe uncovered 4,000-year-old Stone Age human burials, and linguistic ties between Somali and the oldest Cushitic tongues serve as living proof of a long historical continuum, reinforced by unbroken oral traditions among tribes and saints that preserve ancestors’ names and deeds across centuries. Alongside this, the ruins of ancient ports like Zeila and Barawa, and cities such as Opone and Sarpion mentioned by early travelers, tell of Somalis as traders and seafarers connecting the ancient world from the Red Sea and Indian Ocean to India and China. All this evidence affirms that Somalis were never outsiders in the Horn of Africa—they were its guardians, builders, and heirs, shaping its cultural identity and giving it a unique rhythm. To accept the false narrative of migration is not merely a misreading of the past—it is a denial of the soil that holds ancestors’ bones and a rejection of the enduring continuity of a civilization deeply rooted in time, one that gave the Horn of Africa its strength, meaning, and place in the heart of human history since its earliest chapters.

Just like the false narrative of migration, there is another story slowly woven—found in the books and reports of colonial powers and often repeated without scrutiny: that Somalis lived in a stateless society, and that the concept of the modern state was a gift handed down by European conquerors. Yet when we walk through the old alleyways of Mogadishu and hear the echoes of waves that once carried merchant ships to its ports, or when we visit Zeila and Barawa where minarets rose and markets thrived, a different history begins to unfold—a history that reveals Somalia as a vibrant heart within the body of the Islamic world. Here, Muslim sultans once ruled, and from here emerged powerful states and sultanates like the Ajuran and Adal, extending their authority over land and sea and linking the Horn of Africa to the wider world through the Indian Ocean and the Red Sea. In the countryside, under the shade of acacia trees where elders gather in their councils, or in the evenings when poetry echoes with customary law, another face of Somali governance appears—not a society without order, but a living network known as xeer, regulating justice and restoring peace, guided by the moral compass of Islam and bound by social contracts among clans and lineages. Far from primitive, as the colonizers claimed, these were sophisticated institutions that enabled a vast and mobile society to maintain security, organization, and adaptability. When colonial powers arrived, they drew artificial borders and imposed alien administrations—not to create a state from nothing, but to bury or replace the existing system. In doing so, they left behind a misleading narrative that still awaits correction today.

A recurring distortion in Somali history lies in the claim that clan culture stands in opposition to the modern state, and that kinship ties themselves are obstacles to progress. In reality, Somali tribal culture possesses a unique flexibility that allows it to engage cooperatively and adaptively with the modern state—provided this engagement respects traditional structures and deeply rooted social symbols. Clans are fully capable of participating in state institutions, contributing to decision-making, and offering social and political support when their identity and status are acknowledged, and when they are treated as partners rather than subordinates. Conversely, the same culture shows strong resistance when it is marginalized or suppressed, or when state modernization efforts aim to erase its values or impose foreign models on society. The real issue has not been the existence of clans themselves, but their manipulation—first by colonial administrations that divided and ruled, and later by political elites who transformed kinship into a tool for political ambition and mass mobilization. What is often portrayed as a source of division is, at its core, a system of belonging that—if wisely managed—can serve as the foundation for an inclusive and resilient state. Such a state would be capable of balancing tradition with modern challenges, while preserving identity, culture, and social continuity in the face of pressure from centralized authority or forced modernization.

Similarly to such repeated distortions, Islam has often been misrepresented as an obstacle to building a modern state in Somalia, while the reality tells a very different story. In the calm dusk of Somalia, the bustling lights of Mogadishu’s markets flicker as vendors raise their voices above the whispers of the wind, and the call to prayer echoes, reminding everyone that religion is inseparable from daily life. This lived reality stands far from the false claims; colonial powers sought to transplant the European historical experience of statehood into their colonies, importing governance models, administrative structures, and Western political thought, stressing secularism and the separation of religion from authority, while imposing modernist visions disconnected from traditions and clan ties, seeing Islam as a unifying force that might obstruct their colonial project. Yet, under the moonlight in villages, elders sat to resolve disputes and teach children in Quranic schools, while Sufi orders that had once organized resistance against foreign invasion were remembered, revealing that Islam was never a barrier but rather a unifying power and a form of cultural resistance. It encouraged the building of just states but rejected the secularization of Muslims and the removal of religion from public life, offering instead a moral compass and cultural foundation that enabled Somalis to reconcile their traditions with the requirements of a modern state. This proved that local history and values could harmonize with modernity to build enduring political institutions while safeguarding the cultural and religious identity of society.

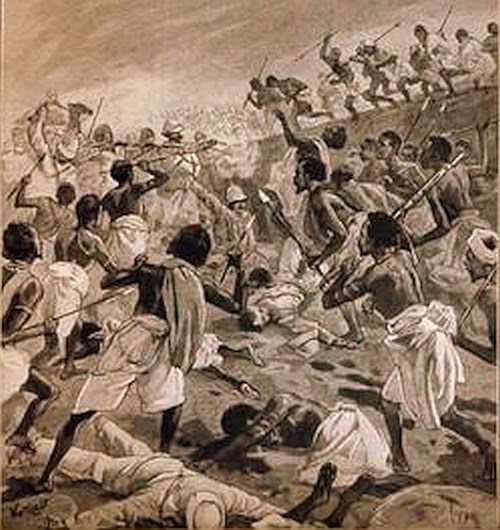

Another narrative that requires correction is the frequent portrayal of all Somali resistance to colonialism as “nationalist.” To stand on the dusty plains of Taleh, where the ruins of Dervish forts still watch the horizon, or to recall the uprisings of Banaadir farmers who resisted Italian conscription, is to witness struggles that were not born of modern nationalism but of Islam, sovereignty, and collective honor. These people defended their land, their faith, and their dignity against foreign invasion, without articulating the abstract idea of a nation-state as defined in European political philosophy. Nationalism, in reality, was itself a product of colonial modernity—spread through mission schools, colonial administrations, and a small stratum of newly educated elites who learned the language of the colonizer. The first genuine expression of nationalism did not appear until 1943, when a group of Somali youth in Mogadishu founded the Somali Youth Club. In their dimly lit meeting rooms, a new vision was born: the idea of uniting all Somalis under one modern state. Confusing early resistance with nationalism flattens history, erasing the jihad led by religious scholars, the collective solidarity of pastoral clans, and the blood shed for dignity before nationalism even had a name. Correcting this narrative allows us to see two distinct yet connected threads clearly—the deep-rooted traditions of resistance that preserved Somali cohesion, and the later nationalist awakening that transformed this legacy into a political project for independence.

One of the shortcomings of historical narratives is the neglect of Somali women’s contributions to the nation’s historical development, a silence that erases their vital role in building and sustaining society across generations. During the civil war and its aftermath, women’s roles expanded dramatically: they managed households and camps, preserved traditions, raised children amid chaos, and became the backbone of communities in the absence of the state, patiently weaving together the torn social fabric. They also participated in political processes through involvement in local councils, clan negotiations, and community initiatives aimed at rebuilding state institutions. Too often portrayed as passive observers, the reality was far different. In village courtyards, mothers transmitted oral traditions, taught children the Qur’an and poetry that preserved collective memory, instilled values that bound generations together, and even led communal political dialogue when formal structures failed. When disputes escalated among men or compromises faltered, their wisdom often guided negotiations and supported reconciliation, sometimes with greater success than men themselves. During the resistance against colonial invasion, women stood at the frontlines—carrying supplies, treating the wounded, and at times taking up arms to defend land and dignity. In pastoral life, in marketplaces, and in displacement camps, their voices directed resource distribution, mediated clan reconciliations, maintained family cohesion, and shaped political decisions that influenced both local governance and the emerging Somali state. Far from the erasure that some historians have imposed, Somali women were both the silent architects of daily life and visible leaders in the story of the nation, shaping history through patience, resilience, and political engagement. Yet their contributions remain marginalized, awaiting deliberate recovery and reintegration into the broader Somali historical narrative—so that the nation’s story may be told as it was truly lived, through their endurance, courage, and leadership.

Correcting these narratives is not merely the work of dedicated researchers; it is a political and cultural necessity that speaks to the very soul of the nation. The stories a people tell about themselves are the compass by which they chart their future—stories that can either diminish them into false shadows or lift them into the light of truth. For Somalis, reclaiming their history means more than setting the record straight; it is an act of restoring pride, recovering dignity, and envisioning a state rooted in authenticity rather than distortion. By revisiting these misrepresentations and weaving silenced voices back into the fabric, Somalis can shape a collective identity that is balanced, inclusive, and empowering—an identity that honors the past while guiding the future. The struggle over Somali historical narratives is inseparable from the struggle for the nation’s spirit itself; it is both a moral and political duty that affirms that only Somalis can define themselves, honor the sacrifices of their ancestors, and craft a future anchored in the truths of their past. This struggle lives on in every poem recited, every chronicle written, and every story passed to the next generation, where the legacy of resistance endures and proclaims that Somalia’s history belongs first and foremost to its people. This battle carries profound moral weight, seeking justice for those erased from official records, recognition for the movements and communities long ignored, and the restoration of dignity, identity, and continuity. At its heart, it is a quest for truth—not a static record of events, but a living dialogue between past and present that shapes how societies understand themselves and direct their future. Every story preserved or reclaimed becomes an act of moral responsibility, ensuring that memory functions not only as a record of what was, but also as a guide to what can be, empowering generations to learn from history, resist distortion, and affirm their rightful place in the ongoing narrative of their people.

In the modern world, the battle over historical narratives unfolds across countless arenas—school textbooks, the media, public monuments, oral traditions, and digital archives all become contested spaces where stories are written, challenged, and defended. Societies that fail to engage in this struggle risk surrendering to distorted memories, repeating past mistakes, or absorbing histories that serve the powerful rather than the people themselves. By contrast, those who reclaim their narratives and confront distortion cultivate resilience, strengthen collective identity, and foster a conscious citizenship capable of making informed choices rooted in historical awareness. In this way, every act of preserving, interpreting, or recovering memory becomes not only an affirmation of truth but also a foundation for collective empowerment, ensuring that memory shapes the present responsibly and guides the future wisely. Ultimately, the struggle for historical narratives is not merely an exercise in remembering the past—it is a decisive act of shaping the present and claiming the future. It is a stark reminder that history is never neutral, that every story told carries power, and that silence or indifference allows others to define reality on your behalf. To engage in this struggle is to claim ownership of collective memory, to confront distortions, and to ensure that the lessons, victories, and struggles of the people inform contemporary decisions and guide future generations. In this sense, the fight for history is the fight for agency, identity, and the right to define how a society understands itself and its destiny—where every narrative reclaimed or rewritten becomes an act of resistance and a direct contribution to empowering the nation to command its past, comprehend its present, and shape its future.